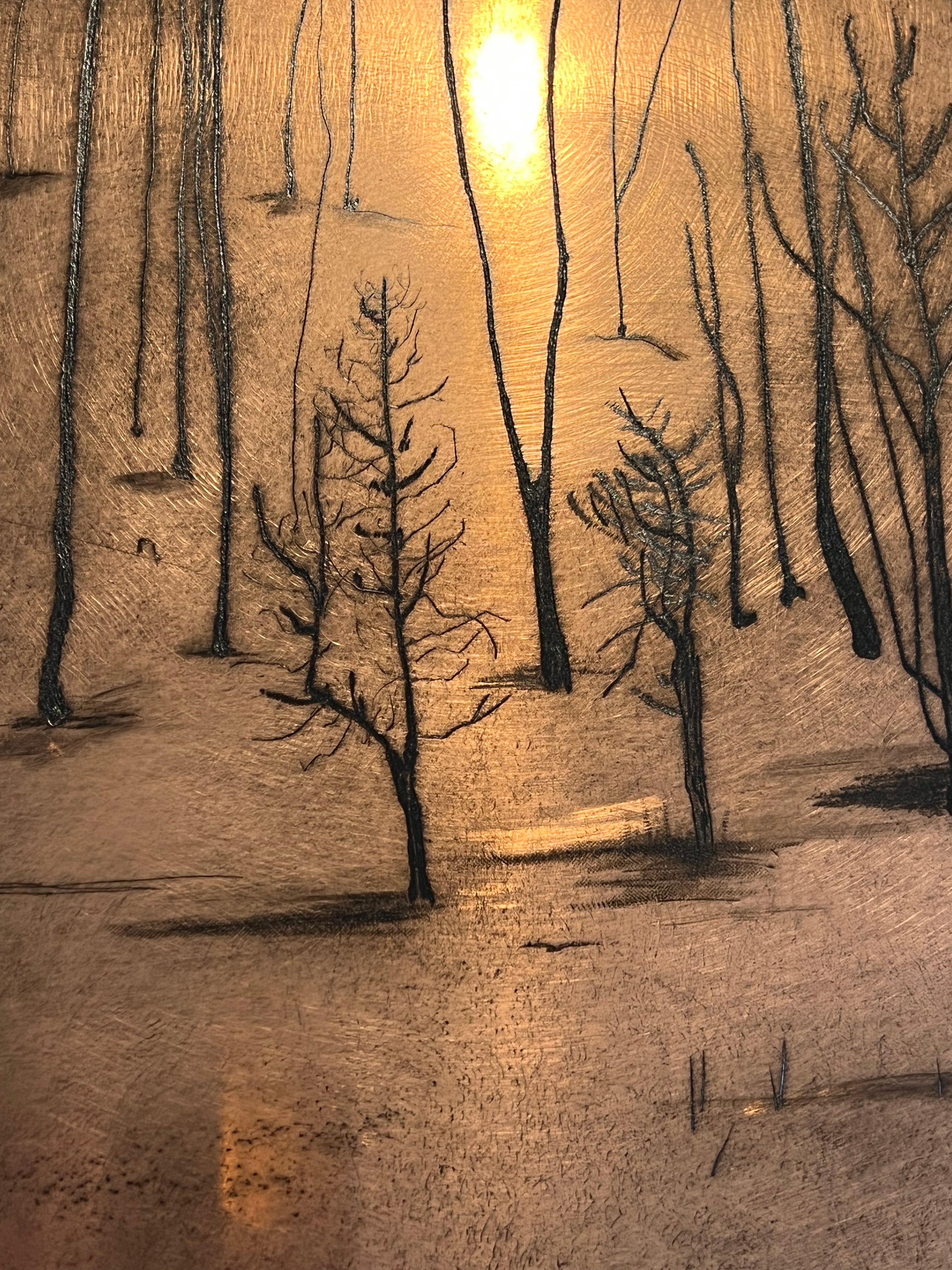

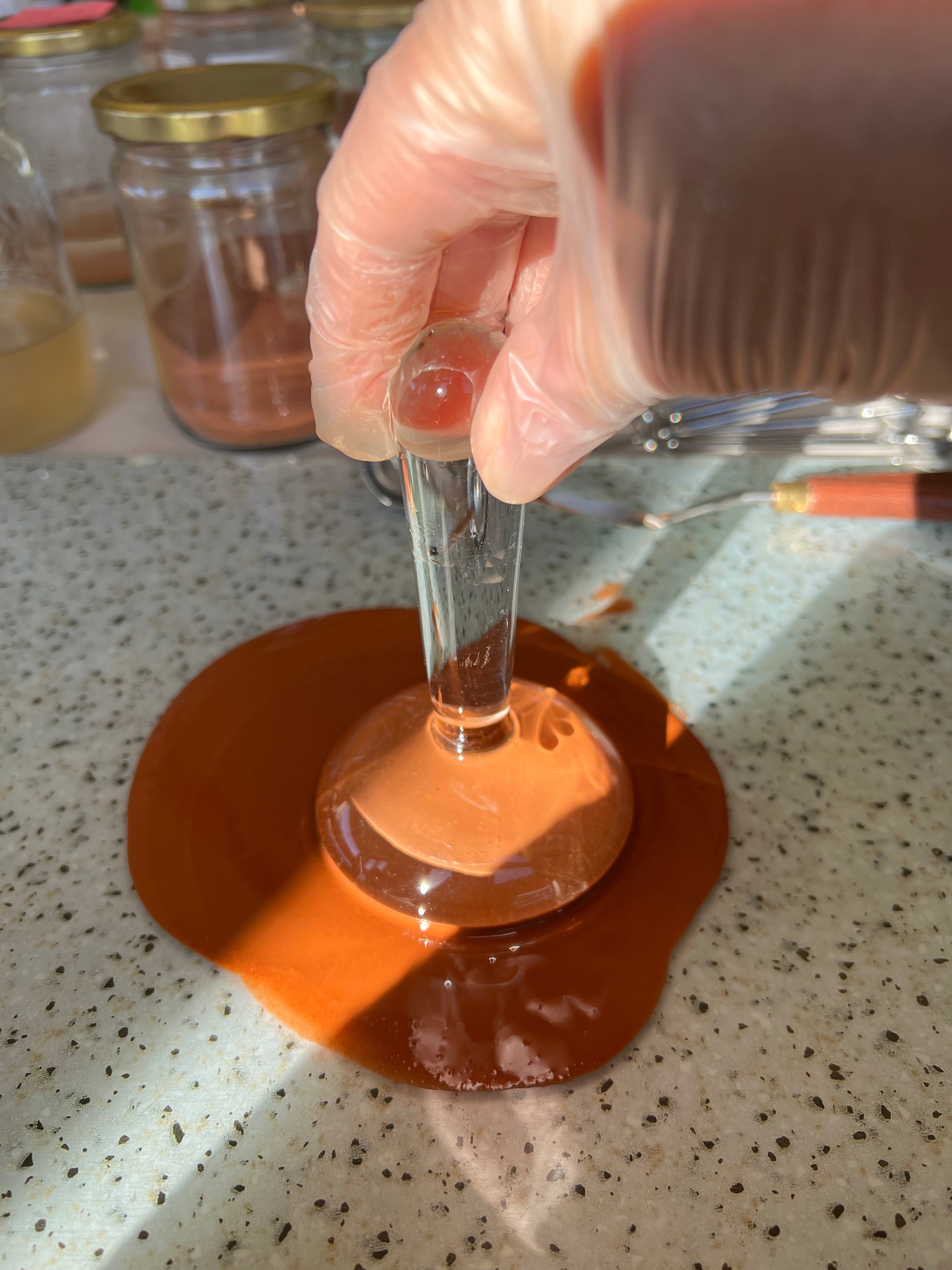

Place is really important to me. Connecting with the landscape, finding connections in the community. I relocated south from Wellington in 2021 after 16 years living there in Breaker Bay on the south east coast. In Wellington I ran a works on paper gallery for many years before having a family. The move south saw us initially spend a year in a small town amongst the mountains in Northern Southland, I am now based in Dunedin. As far as studios go, I have a print studio set up in Northern Southland where I’ll go for blocks at a time an produce a big body of work. I also work from a space at home in Dunedin, preparing plates and exploring drawing with pigment and silverpoint, with some emerging experimentation with how printmaking intersects with jewellery making. I enjoy teaching printmaking classes to the public when the opportunity arises and I have a gorgeous small etching press that I travel with under the name ‘Little Prints’.

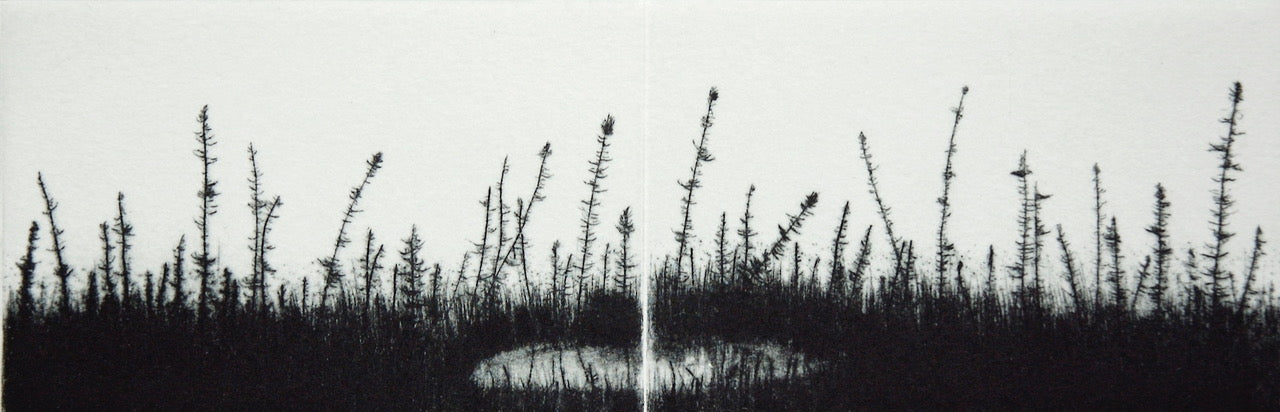

Kyla Cresswell’s constellation of work, Tracing the Land, is also concerned with memory embedded in the local landscape through Waihōpai | Invercargill’s links to at least five different ecosystems: mixed podocarp forest, riparian, estuary, wetland, bog. Between 1865 and 1965, a quarter of the original Kōreti/New River Estuary was reclaimed. The Waihōpai Arm, where Chief Surveyor J. T. Thomson chose to establish Invercargill in 1856, has been the most impacted, with approximately 75% of the Arm reclaimed.* Soil analysis shows the extent of wetland loss since settlement began – roughly 90 percent of pre-settlement wetlands in Aotearoa have been destroyed by agricultural and urban development, reducing the land’s ability to sequester carbon and cope with flooding. Wetland areas also improve water quality and provide unique habitat for threatened birds, fish, and plants. It goes without saying that wetland drainage and vegetation clearance are incredibly harmful to the entire ecological system.

* Jane Kitson, Koreti/New River Estuary Ngāi Tahu ki Murihiku values, environmental changes and impacts: Report for the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, November 2019.